Just a few years back, it was a given that anyone could casually take a wooden riverboat from the UNESCO town of Luang Prabang and head north 150 miles up the Nam Ou [River] to Phongsali and nearly all the way to China, passing Nong Khiaw and Muang Ngoi along the way.

For decades, the stretch of the Mekong tributary between Pak Ou Caves (just north of Luang Prabang) and Nong Khiaw had been a popular tourist route, providing legitimate and reliable livelihoods to thousands of residents in this otherwise remote corner of Laos where opium cultivation once ruled not so long ago.

And, for hundreds of years prior to the arrival of tourists, the Nam Ou had been a critical lifeline — second only to the Mekong — for trade and transport across Northern Laos.

Then, just over a year ago — around the time we moved to Laos — that all came to an abrupt end. Construction on the first of seven hydropower dams financed by China forced the closure of the waterway south of Nong Khiaw to Luang Prabang. Then, just last month, construction on another dam just 12 miles upstream from Nong Khiaw halted boat traffic to the north. It’s ironic to think, in Luang Prabang province of all places, where so much time, effort, and resources are constantly being devoted to saving Lao heritage in one corner, so much is being done to permanently destroy it just a few miles away.

Consequently, Nong Khiaw’s riverboat industries are dying — a quick and painful death, nonetheless. The effects are already obvious in town where dozens of boats sit idle along the banks of the Nam Ou in the center of town, as if waiting for something to change — which isn’t entirely unreasonable. After all, construction on Xayaburi, the most controversial of Laos’ dams, was halted indefinitely in 2012 following strong protests by the governments and residents of Cambodia and Thailand. But damming the Mekong — a river which is shared by six nations — has proven a far different matter than damming a tributary that, for all intents and purposes, lies completely within the borders of just one nation.

While it remains to be seen whether all seven dams along the Nam Ou will be fully realized, completion of just a couple are enough to alter the economic, cultural, and environmental landscape of the entire region for generations — and construction efforts are well underway.

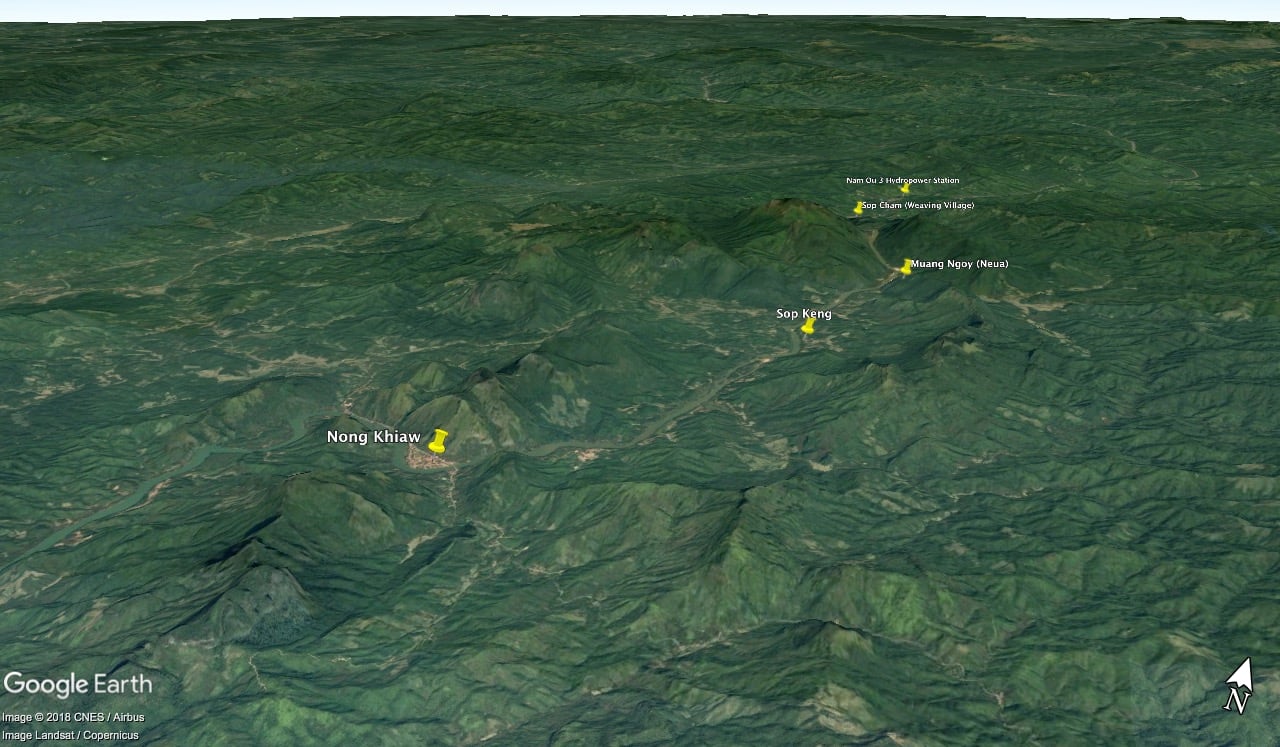

Today, the plan is to hire a boat driver in Nong Khiaw to take us to the farthest community north along the river as is still possible at the close of 2017. Sop Cham, more commonly referred to as ‘the Weaving Village’ by local tour operators is the isolated community that now bears this [not entirely] welcome distinction.

The journey will take us approximately 60-90 minutes in a narrow wooden motorboat, depending on current and wind. On our return trip down river, we’ll stop off at Muang Ngoi [Neua] and possibly Sop Keng, an ethnic minority village with a scenic waterfall hike.

The ten mile stretch of river north from Nong Khiaw is said to be the most dramatic on the Nam Ou, and immediately after leaving town it’s easy to see why. We’ve got limestone cliffs jutting a thousand feet straight up on both sides, framed by dense green jungle. Today’s low-lying clouds and fog enhance the drama and mystery of our surroundings.

Our boatman drives the route confidently, demonstrating an intimate familiarity with the geography, but also the seasonal nuances of the river. At one point, we turn into a large bend in the river, compelling the captain to make a dramatic diversion, hugging the left bank.

For a split second we begin to question our driver’s skill and competency — that is, until we come clear around the bend and spot a packed tourist boat beached in the center of the river. Our boat slows immediately, the two captains signal and yell to each other, our driver nods, and we continue on, leaving the stranded boat behind.

We certainly felt a great deal of unease leaving these people behind in the middle of the river, but in these situations, you have to trust the boatman, and from both captains’ body language, it was apparent the captain of the stranded boat had things under control and our assistance was not needed.

Onward.

After about an hour, we approach Muang Ngoi. As is often the case in Laos, it is apparent there’s been some mis-communication between the boat office agent (that we arranged the boat through) and the boat captain, as he makes an obvious turn towards the dock. We motion to the captain to keep going — ‘Sop Cham!’ ‘Sop Cham!’ Naturally, this compels the captain to ring the boat office agent to clarify the day’s plan. After several minutes of animated exchange, the boat captain hangs up the phone, fires of the motor, and steers the the bow back upriver.

Leaving Muang Ngoi behind, we immediately notice a change in the boatman’s driving. We’ve slowed considerably, and we can see the captain carefully scanning the surface of the water. Our suspicion is we are now in less familiar territory. We continue north.

Twenty minutes later, we arrive at ‘the Weaving Village.’ Once prime real estate along the busy Luang Prabang – Nong Khiaw – Muang Khua tourist route, the Sop Cham river bank is completely deserted when we arrive. I find myself wondering just how many ‘tourists’ make there way up here now, just miles shy of the Nam Ou 3 Hydropower Station (i.e. dam) — the end of the line. What I can say for certain is that we saw no other tourist boats or passengers land here (or on this stretch of river for that matter) the whole time we were up here (~2 hours including transit), in the midst of peak season.

So, here we are in the remote ‘weaving village’ of Sop Cham on the Nam Ou. What’s strange about this village from the outset is that, while Lori and I have visited many ethnic villages in Laos where copious amounts of weaving is produced, this is our first visit to a so-called ‘weaving village.’ So, why the distinction? Well, while a great many of Laos ethnic hill tribe groups have a collective history of weaving, the primary ethnic group on the River Ou — the Khmu people — do not. Rather, the Khmu have primarily engaged in mountain slope rice cultivation and river trade throughout their history. I suppose that’s what makes this village special — it’s not a Khmu village in a Khmu majority region.

So who are these people, then? Well, it’s a bit of a mystery, to be honest. What we do know is that this village is relatively new, and populated by a community that was relocated here by the government for unclear reasons. What is clear is that these people can weave!

We also notice a serious lack of men in the village, but a TON of kids. Which leads us to conclude that the men are out doing something other than weaving, but what is unclear. They sure aren’t on the river.

The kids in the village were quite taken with Noe, much more than he was taken with them. Things vacillated between ‘We Are the World’ moments and ‘Lord of the Flies’ moments, which made the whole affair heartwarming and unsettling at the same time. One moment, it seemed the kids wanted to adopt Noe…the next, it was as if they were devising various experiments they could conduct on the falang noi…and then back to loving on him.

Noe certainly had his fans, but this little girl was not one of them.

At one point, two boys take Noe’s hands and walk off with him. Curious (and…being his parent and all) I follow close behind.

The group follows the path out of town before turning up a small hill to the school. Awe, I thought. The kids just want to show him where they go to school. That’s nice.

They cross the schoolyard, beelining it directly to a wooden structure. Then, together, start to lead Noe up the ladder to the plywood slide.

Fortunately, daddy was not far behind. I grabbed his arm and led him down the baby slide of death for a soft landing. If Noe had been just a bit older, he may have been able to navigate the makeshift slide with no problem. But he’s not quite there yet.

On our way back to the boat (after buying a healthy amount of beautiful handwoven scarves and runners between the four of us) we noticed two children, about Noe’s age, marching up the mud steps from the river to the village — totally unattended. I often wonder how Noe’s life might be different if we had ended up in a village rather than the capital for these two years. He’s becoming such a city boy. Perhaps some day in the not too distant future we’ll be able to offer him a rural living experience not unlike Sop Cham.

Leaving Sop Cham, we turn south for Muang Ngoi. It’s all downriver from here.

We pass water buffalo — both the black and the white variety.

And before we know it, we’re in Muang Ngoi — or more accurately, Muang Ngoi Neua, given that Nong Khiaw was the original Muang Ngoi of the region (yes, it can get confusing).

I certainly was not expecting this. We follow the steps from the boat landing up into town and are greeted by the most surprising and wonderful assortment of colors, fragrances, and textures — a model village if there ever was one. The village is carefully planned out and every square inch is neat, tidy and bursting with flowers and colorful foliage. Every few meters there’s a perfect little restaurant, bar, coffee shop, or guesthouse — not to mention sign after meticulously hand-painted sign directing visitors where to go, or what to see and do.

Lori and I originally planned on overnighting here with our visitors, but ultimately knew it would be much easier (and more enjoyable for all) if we limited our lodging moves as much as possible. That way, we wouldn’t have to pack up and setup Noe’s portable crib so many times, and we’d limit the number of adjustment nights with Noe (which are often unpleasant). So, an overnight in Muang Ngoi got the axe. But I would certainly recommend staying here. It seems more than worth it.

We followed the road through town until it ran down into a rushing creek.

On the right, a series of wood and bamboo bridges led pedestrians over the stream and farther afield. On the left, a cave.

I stayed near the mouth of the cave with Noe while Lori, Jason, and Caroline disappeared into the underworld. Some time later they reemerged with tales of pirate skeletons and treasure chests…or a couple of large chambers and tight squeezes. You decide.

After a fulfilled couple of hours in Muang Ngoi, it was time to head back — but not before a quick stop in Sop Keng, a small ethnic village known for it’s waterfall hike. It was too late in the day to do the entire hike, but we were able to walk about twenty minutes of it before having to turn back.

At the end of a long day on the river, we managed to make it back to Nong Khiaw just as the light was beginning to fade.

This is not a part of the world that is familiar to rapid change — and indeed, prior to the construction of the dams, not much had changed in this valley over the past couple of decades.

But as the hydropower plants go online, more are constructed, and water levels begin to rise, change will come, and it will likely come fast. Just a few years back, full-time electricity arrived in the valley, and currently, a new highway along the river is stretching its way north. In a matter of years, a high-speed rail connecting the region with China, Vientiane, Thailand and beyond will begin operation.

Sure, people of this valley deserve progress and modernization as much as anyone else, but at what cost to their livelihoods, natural resources, and valued cultural heritage?

On our way up from Luang Prabang to Nong Khiaw by road, we passed a half dozen or so communities marked for relocation to higher land. Most had big white ‘X’s painted on every structure in the village, while others had already vanished. We passed an entire village of foundations and rubble, most still bearing the ceramic tile where the kitchen and bathroom once stood.

Change is coming, and it’s coming fast. And when the floodwaters, and the bullet trains, and the Chinese tourists finally inundate the valley, the heart and soul of the Nam Ou and the communities it nourished will have long vanished, and there will be nothing left to come for.

Beautiful photos as usual, but such a sad story overall. Can nothing be done to save the culture of these people?

Thanks Jan! You raise an excellent, yet complicated question. Unfortunately, international development is a complex issue, especially when dealing with competing interests.

Unfortunately, so long as the Chinese are allowed to operate and “invest” in Laos with impunity, traditional culture, heritage, livelihoods, ancestral land, whatever gets in their way, stand little chance of survival beyond the next decade. These villagers have literally NO say in what is happening, and Laos culture is such that speaking out is highly taboo.