Inhambane to Linga Linga

Linga Linga was a place which occupied my dreams even before I left Mozambique. While generally a challenge to reach, I must have visited the idyllic remote peninsula a half dozen or more times while living in Morrumbene. While my day-to-day living in Morrumbene was far from a walk in the park, I counted myself among the very fortunate to be living in such close proximity to beautiful beaches. I don’t remember going to the beach more than once a month on average, but felt I was able to sufficiently take advantage of my central location to the water, nonetheless — 3 hours (30km as the crow flies) to Tofo or Barra Beach, 3-6 hours north to Vilanculos, or 2-3 hours to Linga Linga from Morrumbene pier.

The first time I visited Linga Linga was something of an accident. Two other nearby Peace Corps volunteers met up with me in Morrumbene one Saturday with the intention of relaxing and hanging out at my place. After an hour, however, we were growing restless and started entertaining other ideas. Lindsay had heard from another volunteer that there was a nice beach named Linga Linga not too far from town, and the best way to access it was by catching a public dhow (traditional sailboat) at the pier in Morrumbene. Being a particularly hot and humid mid-summer day, this appealed tremendously to us. We set out to find our way to the nearby beach with the intent of being back in Morrumbene by nightfall.

To make a long story short, we did find a beautiful beach which far surpassed our expectations, but the journey took much longer than any of us had imagined — 30 minute walk to the pier, 1-2 hours waiting for the dhow to fill up with passengers, 3 hour ride to the village, and another 2 hours bushwhacking our way to our final destination. By the time we reached Lucio’s place, the sun was already setting and it was quite evident we wouldn’t be returning to Morrumbene until the next morning.

Luckily for us, word spread throughout the peninsula that Malungos (i.e. white people/ foreigners/ etc.) had been sighted and someone was eventually dispatched to fetch us and bring us to where we wanted to go, even if we hadn’t yet come to the realization that that somewhere was what we had been looking for. Such is life in Mozambique.

That evening, I met Lucio and set foot on Funky Monkey backpackers (or Lucio’s Place) for the first time. There would be many more trips back and Linga Linga, Funky Monkey and Lucio would all become integral parts of my Peace Corps experience. It was a magical place for me, an experience that had been shared with only a few other volunteers. But it was critical that Lori know this place, and that I return to Linga Linga, before it was gone forever — that is, if it hadn’t already disappeared, which was a real possibility.

Finding Linga Linga generally necessitated transiting through my old town. Due to time constraints and tides, we had agreed that today we’d merely be passing through Morrumbene to the pier. On our return trip, we’d spend the better part of a day exploring and catching up on people and things. As it turned out, this was not to be, as I explain in greater detail in this post. Fortunately, the few errands we had took us a bit around town and past my old reed house, which I was excited to see still stood.

We strolled through the old administrative section of the city, which had undergone a minor facelift in recent years, on our way to the water. The mile-long path leading to the pier (pictured above) was as long and hot as I remember.

The swampy waterfront bore an eery (and almost exact) resemblance to ten years ago. I even recognized many of the old dhows floating in the harbor or resting on the banks.

I often got the sense that much hadn’t changed in decades (or even centuries) in these parts, and my suspicions were at least partially confirmed upon our arrival. It was as if I had returned to a place where time truly stood still, the outside world being of little consequence to the wooden boats, fishermen and boat captains plying these waters. For years, I had wanted to share this all with Lori and now, standing in this place, I began to realize that it might just be a real possibility. Very little had changed, and for us and our purposes, it was absolutely perfect.

Nothing would have kept us from visiting Linga Linga. If Lucio or Funky Monkey or the whole lot no longer existed, I would have still insisted we make the trip. It was a pilgrimage of sorts, and important for Lori as well. I was very pleased, however, to get my hands on a contact number for Funky Monkey (which isn’t easy to come by). I spoke with a woman who confirmed that the place still existed and that we were very welcome to visit. I was reluctant over the phone to ask about Lucio or anything else. Lucio wasn’t exactly a spring chicken back in 2006, and things happen in Mozambique. I didn’t want to get my hopes up for any of it.

We waited for about an hour at a bar near the pier for the tide to rise enough to make the trip. It was the time of the full moon and tides were much more pronounced than usual. So waited, sipping Manica and munching chips while the boat captain made preparations and intently eyed the water level.

As we were sitting at the bar, a poster for Impala beer caught my eye…something new, and pretty cheap. Upon further reading, I was astounded to learn that it was beer made “with mandioca (i.e. manioc or cassava) from our machambas (small family farm).” Mozambique produces some fairly good beers, so I wasn’t chomping at the bit to try cassava beer, but thought it worth a try at some point, just for the experience. We’ll see if I can bring myself to forgoing a Manica or Laurentina Preta for this mystery beverage in the future. Somehow, I think the chances are dim… Vamos a ver.

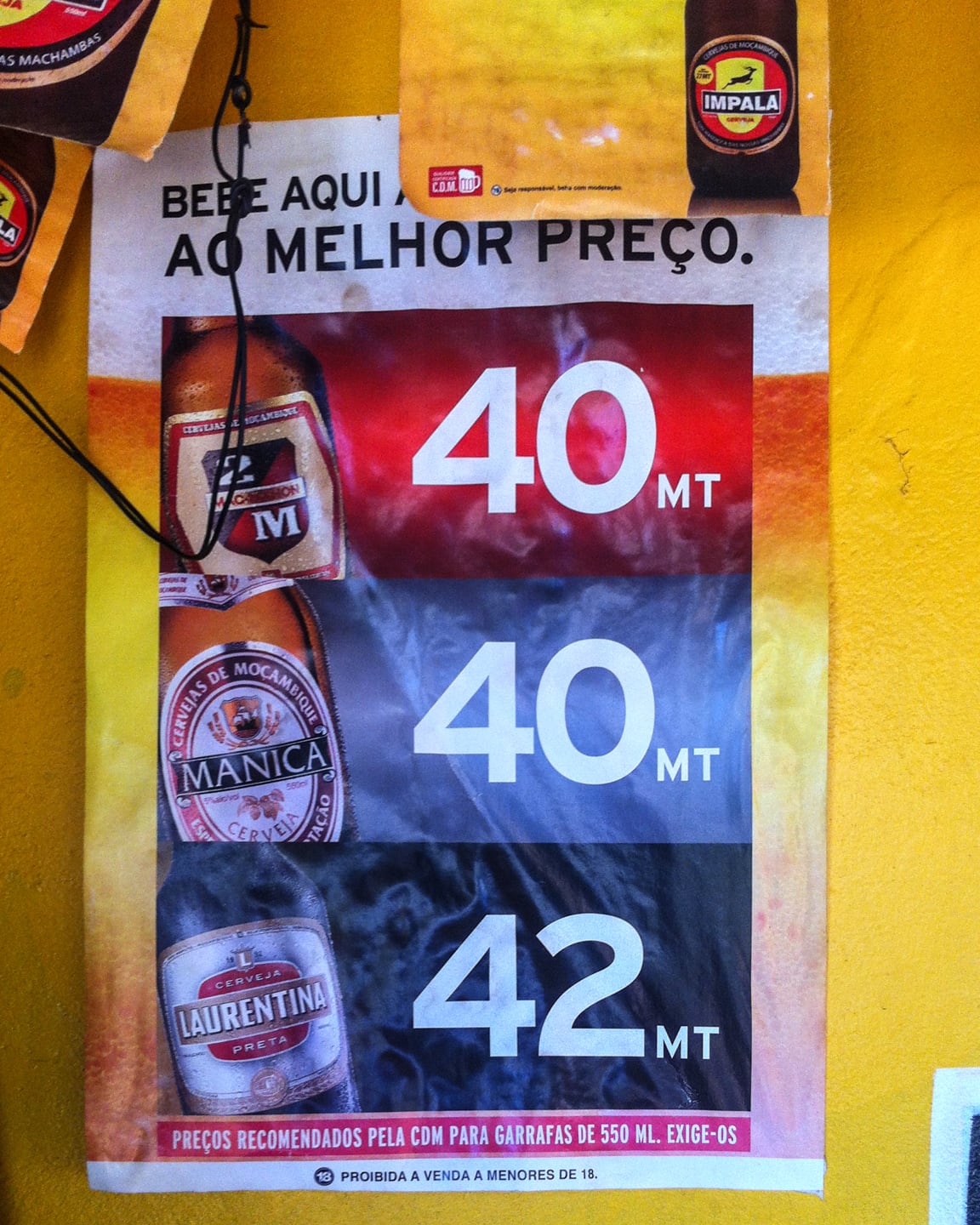

Another poster hanging up at the bar listed Cervejas de Mocambique’s suggested retail prices for three of their most popular products — nearly double what they were eight years ago! In 2006, a 550ml bottle of beer ran you 20-25MT. However, the price increase is still less than average increases across the board, so while many Mozambicans may no longer be able to afford bread, beans or rice, they might still be able to afford beer…which undoubtedly has all sorts of consequences in a place like Mozambique.

But at this moment, I’m trying not to fixate on the social and economic implications of beer pricing. It’s noon and I’m on holiday in Mozambique, so that means Manica time. US$1.30 never tasted so good.

Finally, our boatman gives the signal and we all file down to the dhow. The tide is high and it’s time to get a move on. Suddenly, as often happens in Mozambique, about a half dozen others who had been waiting file out of the woodwork — from trees, houses, latrines — and make their way to the boat. Where these people come from and how they know the boat’s leaving is imminent has always been a great mystery to me.

Generally, there’s very little wind in the protection of the harbor, so the boatmen use stalks to push the dhow along (often into the wind and against the current) until the boat reaches the winds of the bay.

Early on, passengers (mostly women, this time) prepare for the sometimes lengthy journey ahead. This woman is braiding reed used to make baskets and other things.

After emerging into the open bay, the sail is hoisted and set, and the dhow quickly picks up speed. A strong wind pulls tight the sprawling patchwork of sturdy fabrics of varying vintages above, as the captain points us toward the peninsula. It’s midday on the full moon, and the winds are surprisingly strong, much stronger than I remember. We all move to the port side of the boat to prevent it from keeling to far starboard — the angle is torture on our backsides. The waves grow in size and frequency, producing whitecaps — rare for the bay — sending sea spray over the bow, soaking Lori and most of the other women. After about 10 minutes of this, the deckhand adjusts the sail, bringing it nearly perpendicular to the hull, bringing the entire vessel level with the water and immediately improving the ride.

We pass a few other dhows along the way, but no dolphins, dugongs (manatees) or flamingos — regular fixtures in these waters, but not at midday. At midday, it’s just us under the hot African sun.

…and this woman’s huge ball of braided hair, which easily constitutes 30% of Lori’s view on the ride over.

Now on the other side of the bay, we approach the point, as beautiful as ever. Still looks like paradise.

I had read that there were several new lodges built or being built on the point and had worried for years that the essential character of this land would be irreversibly changed for the worse. A few hundred meters off, I could still see the village and traditional reed houses sitting beneath a dense line of high coconut palms. For the moment, at least, my fears were set aside.

After only 1.5 hours sailing (we got there fast due to the intense wind), we were dropped off on a long stretch of golden sand. While we were a half kilometer closer to the point than the village, we were still quite far. This didn’t surprise me, as this usually where the public dhows dropped me in the past, but I thought I had confirmed with the woman I had spoken to that the boat would be able to take us all the way to the point. In the past, the excuse was always that the water level was too low, and when we did convince them to drop us nearer to the point, we ended up having to walk about 500 meters in shallow water to the shore. But today, the water was very high. The boatman, however, did not want to take the boat any farther. It didn’t seem to be a matter of money — perhaps the high winds or simply not wanting to go the extra few kilometers, it was hard to say. Regardless, the boatman informed us that Lucio, himself, was coming to fetch us, so we did that which I found myself doing for half my time in Mozambique in the past — waiting… This was the first confirmation I had received that Lucio was still alive and kicking and that we’d get to see him on this visit, quickly turning frustration into anticipation.

During the best of visits a decade ago, I’d make arrangements for Lucio to take me in the evening on his return trip from Morrumbene to the point. A ride in his tiny fiberglass dhow (something of an anomaly in East Africa) was a real treat. With Lucio at the helm and one of his young and able sons attending to the sail and keel, Lucio’s boat was perhaps the fastest in all of Mozambique. Depending on wind, the journey typically took between 1-1.5 hours, and was never a hardship. I can think of few experiences so vivid and ethereal than those evening trips — as the big ol’ African sun set over the Morrumbene hills, watching mammoth flocks of flamingos flying in unison across the blood-red sky, as dolphins swam off the bow and frolicked in our wake. At nightfall, the sky filled with millions of stars, as bright and vivid as a planetarium. And the icing on the cake? A long psychedelic neon trail of blue-green dinoflagellates, leading from the rudder to infinity.

Unfortunately, this was not to be the case this time around, but I still hoped that perhaps we’d still get to ride the last portion aboard his yellow and white racing dhow. But this was not to be either, as moments later, none other than Lucio himself emerged from the canopy looking exactly as I remember. I had wondered if he’d remember me. It had been nearly a decade, and I imagined he had had many visitors in the meantime. But it was evident that he did indeed remember me — we embraced and all at once the memory became real again, this place and its people still existed, and all was right with the world. I finally had the pleasure of introducing Lucio to Lori. Moments later, we set off through the forest toward Funky Monkey, just as I had the first time I set foot on Linga Linga.

We walked along the sandy road for about 45 minutes until we arrived at the dreaded lagoon. I had hoped that somehow, Lucio, having grown up on the island, had led us on a different path that might have bypassed the large body of water. Here we were, however, standing and peering out over the lagoon. Generally, this meant another 30-45 minutes in the hot Mozambique afternoon until reaching our destination. Yet, it was clear Lucio had another plan.

Moments later, we came upon a canoe, which he promptly untied and pushed into the water. We climbed in and were whisked across the lagoon in a matter of minutes. All of my times on Linga Linga and this was the first time I had ridden across the lagoon — much preferable to walking around it. It turns out, this wouldn’t be the last we’d see of the canoe.

As we approached Lucio’s compound, I was straining to identify anything familiar to me. The first was the fiberglass racing dhow — almost how I remember, but not quite. This one was blue and white. The one I had ridden on (and learned how to sail a dhow on) was yellow and white. The yellow and white dhow, sadly, was up on the bank appearing as if it had been scrapped for parts.

We climbed off the canoe and followed Lucio up into the clearing I remembered so well. To my [pleasant] surprise, very little appeared to have changed. A few new reed huts had been added, but the original backpackers dorm building was still standing and looked much the same as it did ten years ago. In the center of it all, the dining hut was there, also very close to how I remember, save for a new thatch job. But everything inside was the same — the red benches, picnic tables, wall accoutrement…all of it.

The only disappointment, I suppose, was when I noticed that Lucio’s hammock hut, the one that I had patterned my own off of in Morrumbene, had succumb to erosion. Being as it sat up on a sandy bank overlooking the lagoon, I figured it probably didn’t stand a chance. But the hammocks had been saved and moved to the big cashew tree at the end of the property, a much more fitting spot for them anyways.

Sadly, the most conspicuous void had been left by Lucio’s youngest wife and phenomenal cook, Ana, and their two youngest boys, Chevy and Lito, who used to entertain us with their wild antics and help Lucio with fishing and sailing. Ana was away in Beira for the weekend, but the two boys were off at boarding school a few hours away (there’s no secondary school on Linga Linga).

I’ll post pictures of Lucio’s place, etc., in the next post. For now, I leave you with our first glimpse that evening of the Linga Linga coastline.

I was astonished when we emerged from the canopy onto the beach that evening — the beach was very different than I had remembered it. I remember there being quite a lot of vegetation walking out to the beach, but not along the beach — I remember a wide strip of seemingly never-ending white sand running for miles up the coastline. Now, there was hardly a beach, and the beach there was was lined with debris. I knew that erosion had been a significant problem on the Inhambane seaboard and wondered if the vegetation had been planted to preserve the coastline.

Fortunately, we’d learn the next morning that Linga Linga still had its big, beautiful beach, but we had arrived on the full moon and at the highest tide. Low tide revealed an uninterrupted white-sands beach about 100 meters wide, stretching into aqua-blue waters.

But this particular evening, we were treated to one of Linga’s famous sunsets over the bay…and it was still as wild as I remember.

Lucio’s dog seemed to enjoy it as well.

The sunset might not have changed, but the place we were watching it from had a bit. Did I forget to mention that there were now six lodges on the point? That’s six more than there were when I was here last (I don’t generally count Lucio’s place as a lodge — it goes in a category all its own). Well, anyway, that’s one of them (above). Pretty swanky. And not a soul in sight — it is off season, however…fine by me.

Fortunately, the lodges are spread out for the most part and far from Lucio’s place. Yet, it is quite strange to jump back and forth between the two worlds — one moment you’re chatting with Lucio at his home and the next, well, you’re standing in front of a swimming pool and sunset lounge.

On our way back to Lucio’s, we noticed the lagoon had overtaken the road at high tide, essentially cutting off two or three of lodges from the rest of the point. I’m not going to belabor the metaphor here, but you can read what you want to in it. Regardless, the Welcome sign to one of the bars poking out from the lagoon was an interesting juxtaposition. Oh, that whacky moon…