In early February, Bangkok’s toxic smog made headlines across the world. The hazardous mix of traffic exhaust, construction, field burning, and factory emissions forced 450 schools to close for weeks and the Thai capital of eight million to seek refuge indoors.

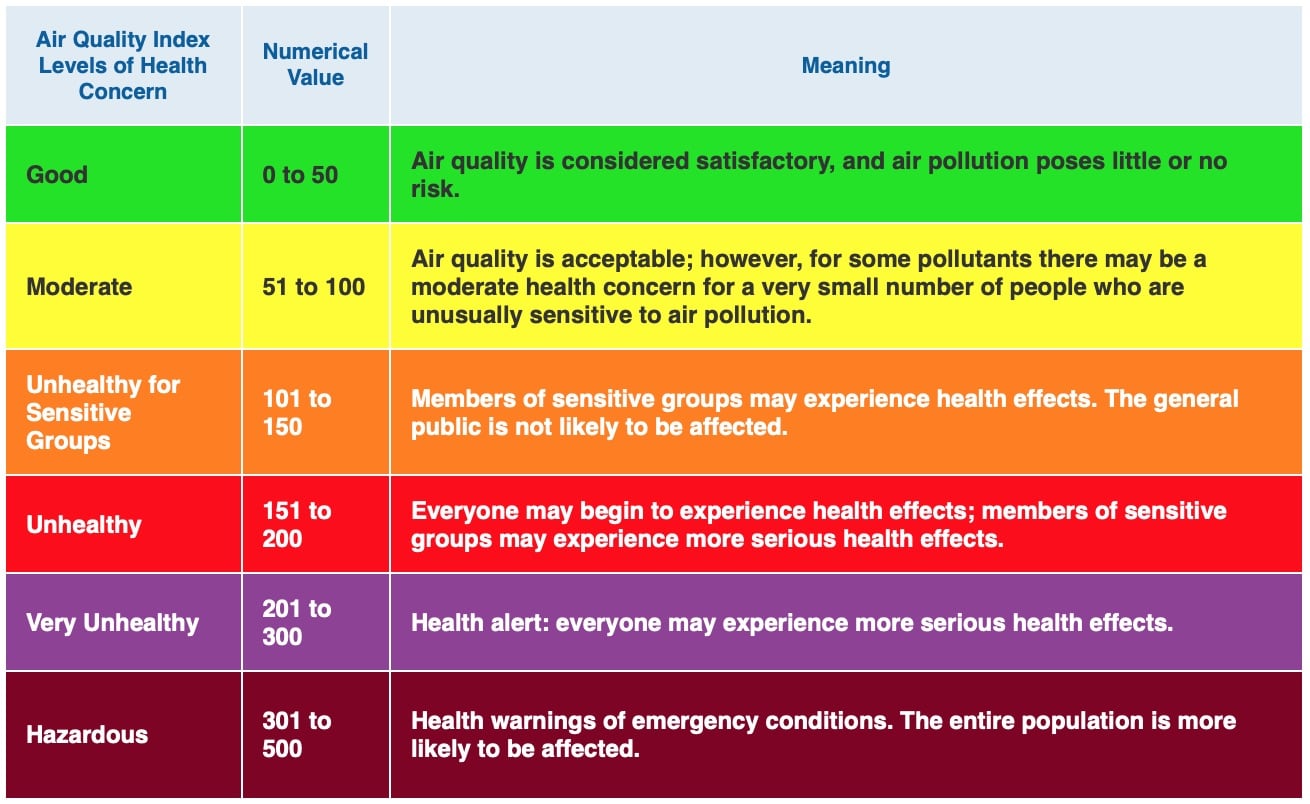

At the height of the crisis, air quality was reported to be the worst ever recorded in Bangkok, with an Air Quality Index (AQI) hovering around 170, which is considered “unhealthy” for the general population. Levels over 100 are considered “unacceptable” air quality.

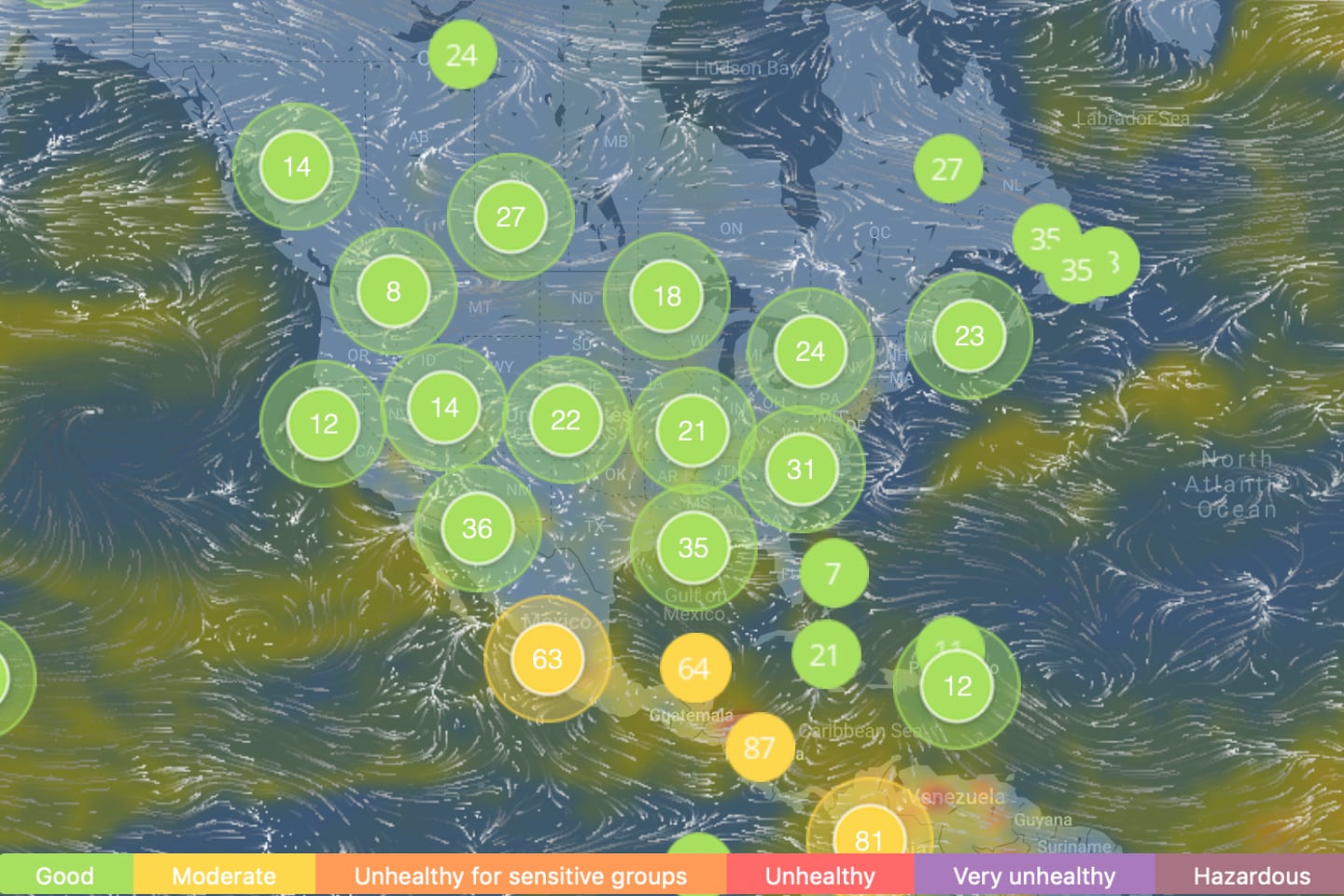

In comparison, this was the AQI in North America in late March 2019:

Being located a mere 300 miles north of Bangkok, people here were understandably worried that the toxic smog might eventually find its way to Vientiane. Yet, by mid-February, air quality levels had returned to normal in Bangkok and residents across the region breathed a collective sigh of relief. Social media in Laos went silent on the topic and that was that.

Unfortunately, Laos wouldn’t be spared for long.

• • •

When people leave the city for a weekend in the country, there’s an expectation that the air is going to be cleaner than the city. We left blue skies in Vientiane on Friday morning and arrived at Lao Lake house on the Nam Houm Reservoir an hour later to find a thick, yellow haze hanging over the lake. That evening we spotted an orange glow in the distant hills — ah, we thought. Field burning. Not uncommon this time of year a month before the rains.

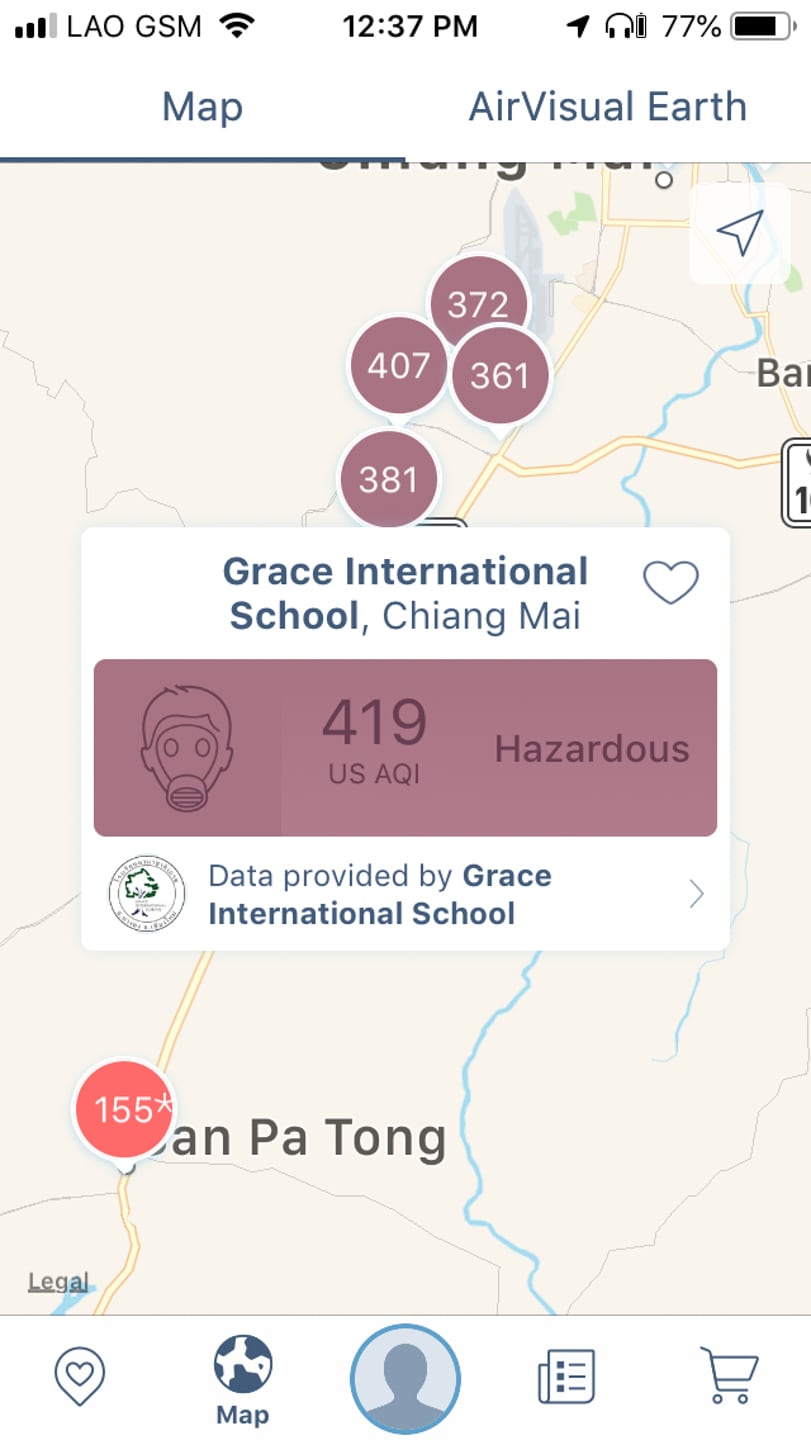

Our local social media feeds, on the other hand, were blowing up with reports and news stories out of Chiang Mai, Thailand, only a few hundred miles to the west. If Bangkok residents thought they had it bad, Bangkok didn’t have anything on Chiang Mai. AQI of 170? Forget about it. Chiang Mai was over 400!!! Now may be a good time to refer back to the chart above. Humans don’t want 170, and they definitely don’t want 400.

If you’ve never lived in Thailand or Laos, you might not be aware just how different the two neighboring countries are in terms of, well, everything.

Sure, the Lao and Thai languages are very similar, and the people of both countries have a shared history stretching back millennia. And, there’s a shared culture of food and music. But the similarities stop there.

In terms of infrastructure, industrialization, development, government structure, communications, and technological advancement, Laos and Thailand simply couldn’t be more different, and the air pollution crisis was a stark reminder. Not only does Thailand have hundreds of air quality monitoring stations, real-time data is publicly available. When AQI levels reach a certain threshold, warning bells sound, government advisories are issued, and officials spring into action to address the issue. Granted, the government was criticized heavily for its failure to prevent the toxic smog emergency in Bangkok, and later in northern Thailand. But the media reported on the issue, residents spoke up, and officials reacted to the crisis.

In Laos, on the other hand, no one had any idea what was going on. The data that is officially collected is not made public, so most AQI scores for the country have to be extrapolated from neighboring countries’ data and satellite imagery. Of course, that didn’t keep people on social media from publishing their own findings and discussing the thick haze migrating south towards the capital.

Then, on Sunday afternoon, we returned from the country to the capital to find this:

This was the view from our upstairs balcony, which didn’t change for over a week. I was out of commission with a sinus infection, so this also happened to be my view for the next several days.

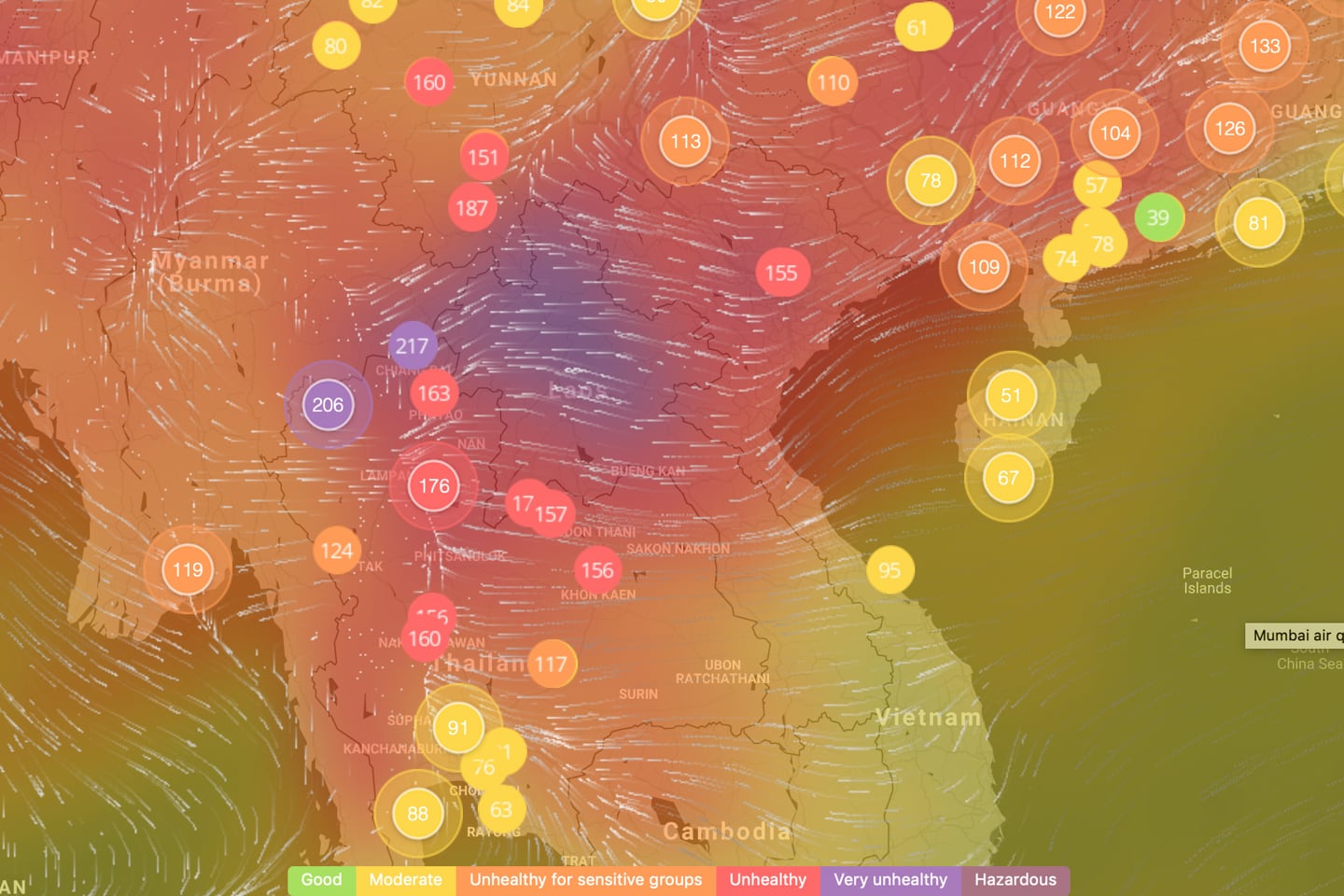

For the first week, there wasn’t a lot of news or hard data to be found. Yet, it was impossible to ignore the thick fog lingering over the city, not to mention the air quality map of the region. That purple splotch with no AQI numbers is central and northern Laos. You remember what purple means, right? Not so good.

Some days the purple blotch would stay north of us. Other days, Vientiane would find itself dead center. Often, it felt like you could literally chew the air. At night, the headlights hitting the particulate in the air seemed like driving through snow flurries.

Unlike Bangkok, however, life went on. While most residents of Vientiane don’t have air quality monitors, the smog was pretty obvious. Few motorbike riders ventured out without masks, and the number of people seen out and about dropped sharply. Noe’s nursery school remained open, but the children were not allowed to play outside for several days.

So, what the heck was going on? Many people seemed to assume that the toxic smog from Bangkok had made its way northward, finally reaching Vientiane. Others who had been following air quality reports out west blamed northern Thailand. Still, others were convinced that the smog bank had drifted down from China, not an unreasonable assumption if you’ve visited in the past decade.

Yet, it turned out nearly everyone was wrong. The origin of this haze wasn’t China, Thailand, or any other country. Nope, this was Laos-made, though none of us had any real way of knowing that because this is Laos where information is centralized and tightly controlled.

According to reports published a week after the AQI spiked, the primary cause of the mysterious haze was wildfires raging throughout central and northern Laos — as of 15 March there are 1,345 hotspots, with several significant blazes reported in the hills northwest of Vientiane. Laos is a sparsely populated country, so most blazes are left to burn unencumbered, until the winds shift or unseasonable rains come our way.

For now, we’re wearing our masks, monitoring the AQI projections on our devices, and keeping our windows shut. I don’t worry about Lori and me, but the boys are another story, as large concentrations of the smallest particulate (PM 2.5) can have lasting and permanent impacts on the developing lungs of children.

For those who might say it’s not worth it living in Laos if it means subjecting your kids to dangerous level of air quality, I’ve got news for you. Toxic air isn’t just an Asia problem or developing country issue, for that matter.

Last summer, the breadth of California met or even exceeded these sorts of AQI levels as a result of the wildfires that devastated the state. The summer before that, the Portland area suffered similarly when the Columbia Gorge fires raged on, in an area often cited as having some of the best urban air quality in the world.

These are only two examples taken from the countless regions across the globe experiencing similar issues, and doesn’t even begin to touch on the critical air quality issues related to heavy industry, burning of fossil fuels, traffic emissions, and deforestation, as cities like New Delhi and Beijing deal with regularly, frequently dipping into hazardous territory.

And to make matters worse, it’s a cyclical effect. More wildfires means more carbon dioxide in the atmosphere; more atmospheric CO2 causes ocean temperatures to rise, which in turn impacts weather patterns, making for more intense weather — longer dry seasons and droughts, and more wildfires.

In reality, we’re fortunate to live in a place like Laos where the air quality, even in the capital, is about as good as anywhere in Asia these days. The winds will eventually shift, or a storm will come, or the fires will burn out on their own, and we’ll be back to our moderate dry season AQI until the return of the monsoon in May.

Yet, for the millions of people living in cities like New Delhi and Beijing, theirs is an ongoing battle with no end in sight — and it is clear that cities like these are becoming less and less exceptional in that respect with each passing year.

On a related note, if you are wondering what else we are doing to combat this year’s particularly bad dry season air quality, we’ve managed to get our hands on a few items that have proven indispensable. Luckily, a friend was coming out to Laos on a work trip and offered to bring out a few things we ordered on Amazon.

Since official public AQI measurements are impossible to come by, we decided to invest in a handheld PM 2.5 air quality monitor. After much research (and a couple weeks of use now), I’m pretty convinced our Temtop monitor would be hard to beat for the price.

In light of Noe’s history of respiratory infections (and that we have a 5-month-old), the Temtop allows us to monitor the air quality in the house to determine if we should have doors open or closed. While we prefer to have the exterior doors and windows open in the house, we’ve found that on particularly bad days, closing the doors/windows and turning on the AC makes a huge difference. We also just learned that Lori’s work will supply an air purifier for our house, so we’ll see what comes of that.

We also got our hands on some PM 2.5 face masks, as the surgical masks everyone wears around here when they’re motorbiking don’t really help much with the really nasty particle matter. I’ve been pleased with my mask for bike riding, even on good air quality days because the traffic exhaust can get pretty nasty as well.

For the boys, we got these fun masks. Noe wasn’t crazy about his at first (mostly because it kept slipping down like in the picture above), but once we got it properly adjusted and he wore it a time or two, he became much better about wearing it when the AQI gets high and we have to be out and about. He also wears it when he rides with me on my bike.

You are taking such good care of your little family! Your pictures really tell the story.

Thank goodness for our air purifier that we have now!