So this happened.

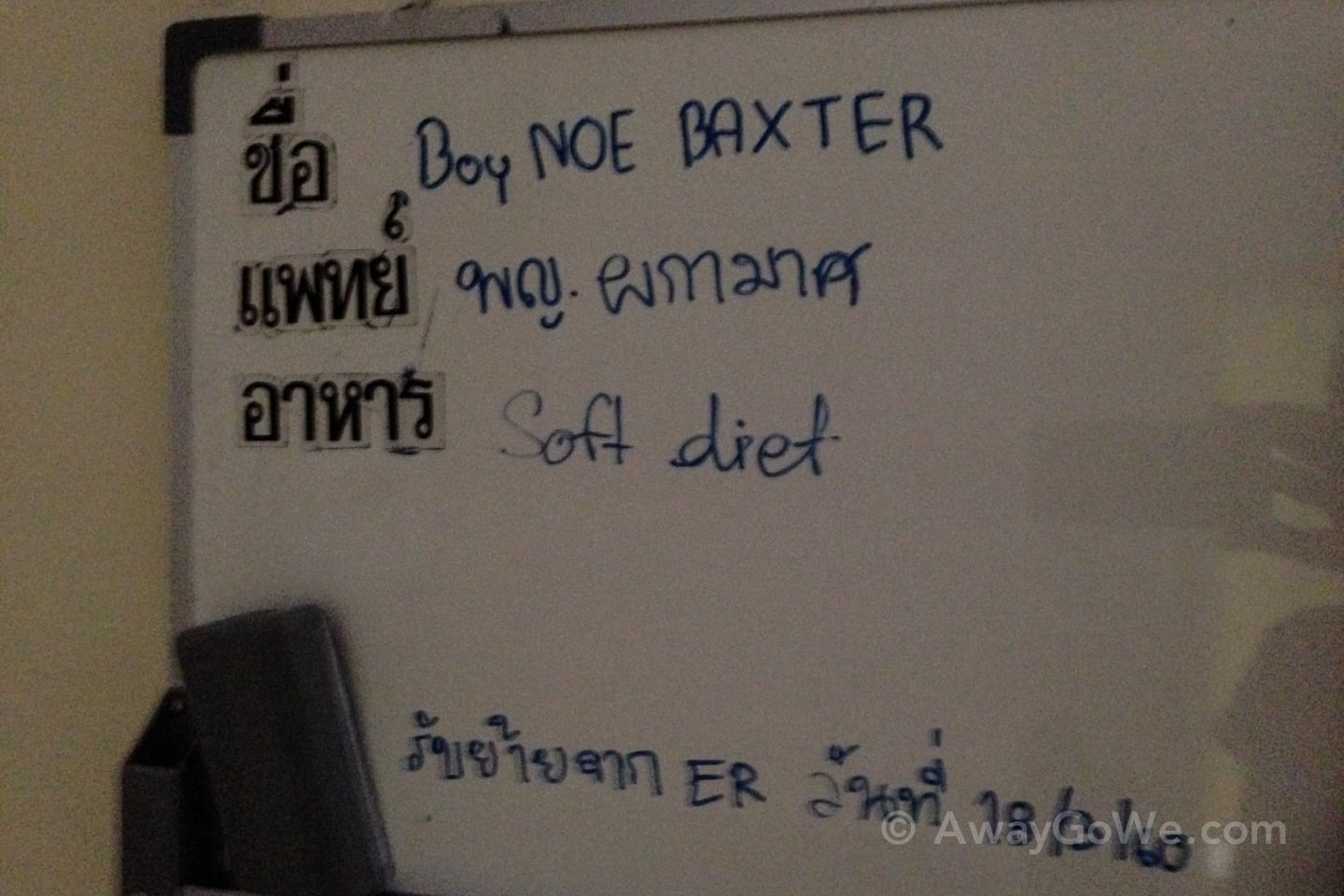

**Spoiler Alert** It wasn’t nearly as serious as the title may suggest, and as of Thursday, March 24th, Noe has made a full recovery and is back to his normal self.

Because we live where we live and the health care situation is what it is, it’s easy to find yourself in an ambulance headed to the ICU in another country even for relatively minor things, so long as there is the risk of complications (and if you happen to be a baby, the abundance of caution becomes more abundant, obviously). Suffice it to say complications are not your friend in a less industrialized country in the tropics with limited health facilities.

Long story short, we chose to transfer to Thailand and do the whole shebang out of an abundance of caution and because there were limited services in Vientiane on the weekend and we are fortunate to have the level of coverage and support from Lori’s work and access to great health care right over the border. Sadly, most people in Laos (and the U.S., for that matter) aren’t so fortunate.

We were staying the night at an eco lodge (see photo above) about 45 minutes outside of the city with friends visiting from the U.S. (I’ll return to that in future posts) when Noe started to act a bit unusual. Initially, we thought he was just overtired after picking him up from the little school he spends a few days a week at. His teachers mentioned he hadn’t slept well all day and that he was fussier than usual, but nothing else concerning. It was the end of the week and we had had close friends visiting since Monday, so it wasn’t a surprise that he might be a bit off. We packed up the car and headed through a freak rainstorm (the first of the season — just our luck) to the rural eco lodge.

As time went on, we noticed that Noe sounded very congested, but unfortunately that’s sort of his M.O. these days, being on a 2-3 week cycle of catching a cold, getting well, then catching another cold. It’s the cold season here and numerous other parents we know in the area have been struggling similarly, so when Noe appeared to be congested, yet again, we thought little of it at first.

But he was also fussier than usual. When Noe is well, he is not fussy. He just isn’t. The kid doesn’t generally cry. He likes people, he likes strangers, he [now] likes all sorts of food, he likes being held, he likes being left alone. His default is smiley and giggly. So when Noe is fussy, there’s generally something else going on. His arch nemesis is the common cold. He hates, hates, hates being sick. All of us do, but Noe loathes it. He turns from being a delightful little angel to a grumpy little curmudgeon (and a bit of a drama queen with his exaggerated coughs, sneezes and his “sick face”). So, we chalked his fussiness up to coming down with [ANOTHER] cold. But this one seemed different, and came on very abruptly.

After settling into our bungalow, he initially fell asleep in his portable crib for about two hours, then woke up wailing. Lori and I did the usual checks. Lori fed him but he didn’t seem keen on eating. After a long while troubleshooting in the middle of night (he was quite unhappy by this point and sounding more and more “congested”), he crawled up on my chest and finally fell back asleep, but only for a couple of hours. By sunrise, Noe just seemed to be hating life. We had been in touch with a pediatrician and had determined that a) something was definitely not right, b) it seemed to be getting worse, c) it didn’t appear to be immediately life threatening but demanded a doctor’s visit.

Under normal circumstances in the States this would have been fairly stressful. Out in a rustic bungalow in a rural village in a country not known for their world-class health care (not to mention with close friends in tow from the other side of the planet with whom we had two precious days remaining), the stress and concern became elevated even more.

Despite our excitement for continuing north to our intended destination with our guests, the decision to turn back to Vientiane was an easy one. Our friends were able to rebook their onward tickets to Thailand for an earlier flight, and Lori, Noe and I found ourselves on our way to the hospital.

And when I say “hospital” in Vientiane, I don’t really mean hospital. There’s a Thai clinic we go to that has a higher level of care and equipment on offer than any hospital in the country. They even have a small, new in-patient facility. Even so, the Thai clinic lacks many of the specialists and treatment options of even a small town hospital in the U.S. For that, you have to go across the border to Thailand. Some of the world’s best medical care facilities are in Thailand, a stark contrast from Laos. Alliance International Medical Centre (the Thai clinic that we go to in Vientiane) is affiliated with Wattana Hospital about a two hour trip south in Udon Thani, Thailand.

Upon arrival at the Alliance/Thai clinic in Vientiane, Noe’s breathing and congestion sounded off, and he was looking increasingly uncomfortable. He also hadn’t been wanting to feed for a while. It was a hot day and dehydration at this point was our primary concern. Nurses took his vitals and the doctor did a full examination. The initial diagnosis was what Lori and I had suspected from our own reading and discussion with the pediatrician on the phone: Bronchiolitis. Noe was put on a nebulizer and, after 18 hours of fussing, he finally calmed.

Noe was showing signs of improvement, but the doctor didn’t like what he was hearing in Noe’s chest. There were also concerns of dehydration, so they started an IV, which would run for several hours. Honestly, one of the toughest parts of this whole weekend was holding Noe’s little hand while he stared at me breathing a bit heavier with lip quivering as the nurses attempted for about five minutes to get a successful IV start in one of Noe’s little feet. The second they had it, he smiled at me. The dude is tough. Almost too tough.

The doc wanted to keep Noe for observation in case there were complications or he didn’t respond to the medication. This being Laos, there were also external complicating factors involved, particularly if Noe’s condition worsened. It wasn’t that the clinic wasn’t typically capable of addressing complications for this sort of thing, but this was a Saturday afternoon — and tomorrow, a Sunday. The level of staff on the weekends — and night shifts on weekends — was apparently not the same as other times. If there were complications in the middle of the night, the providers on staff might not be able to fully address them. Further complicating factors was that the border crossing into Thailand closed at 10pm.

The recommendation, of course, was to transfer to Thailand.

(At this point, I won’t get into how I got my debit card eaten by an ATM and Lori got pulled over by the traffic police for making an illegal U-Turn shortly before taking our friends to the airport to catch their flight moments before we left the country for Thailand as well…yeah, won’t even go there.)

Lori chatted with her boss, logistics officer, and the staff at Alliance and concluded that it was actually more economical and efficient to do an ambulance transfer from the clinic in Vientiane to the hospital in Udon Thani.

And it really was. No joke.

Do you want to know what a two-hour ambulance transfer over an international border cost us?

Nada.

Zero. Zip.

It had nothing to do with our insurance coverage either. Because we kept all of our care in-house within their network (the hospital in Thailand and this clinic were part of the same network), the transfer fee was essentially waived.

Even so, if it hadn’t been waived, it would have cost 3,000,000 LAK, or around US$365. Do you know how much Noe’s total bill came to on the Laos side of the border (including doctor’s fees, medications, IV and nebulizer supplies, and treatment)? US$190. And because Lori works for a respectable European-based international organization and not in the U.S. under our wretched, mucked up health care system, we won’t pay a cent (no co-pay, no co-insurance, no deductible, nothing) for necessary medical care for our child.

When Lori told me we were taking an ambulance to the hospital in Thailand, I thought it was a mere formality that we’d be riding in an actual ambulance rather than a cab or minivan, given that Noe’s condition was concerning, but not life-threatening. But we ended up getting the full meal deal with lights, siren, EMT staff and all.

Apparently, these guys don’t mess around.

Ironically, after six months of living in Vientiane this is how our first border crossing to nearby Thailand unfolds. We had flown to Chiang Mai (Thailand) for Lori’s work in October, but had not yet made the short trip into Thailand, just over the bridge from Vientiane.

It’s not that we haven’t wanted to explore Nong Kai just over the border, or Udon Thani, the larger city an hour farther south. But as of January 1st, the Thai government reduced the number of times non-ASEAN travelers can enter at land-crossings from virtually infinite to just two per year. Also, they drive on the left side of the road in Thailand (versus the right side in Laos). Lori being the sole authorized driver in the family and having no prior experience driving on the other side of the road has been a bit reluctant to try her hand at it.

And, if you’re curious how the transition from one side of the road to the other is managed, between Laos and Thailand, it’s done for you. After leaving the border control and paying the bridge toll on the Laos side, you enter the bridge onramp which magically deposits you on the left side of the road. Easy peasy.

Lori and Noe spent the ride in the rear on the stretcher. Where did they put me? Right up front in the shotgun seat.

I won’t lie to you, I had a blast.

It’s kind of a childhood dream come true to ride in the front of a screaming emergency vehicle with full high-low siren and lights racing through the city streets as vehicles part like the Red Sea. Obviously, I was able to enjoy myself a bit more than a lot of folks, given that the fate of my little boy in the rear wasn’t hanging in the balance. The transfer was more of a formality, done out of an abundance of caution owing to the medical limitations of our resident country and the fact that we were incredibly fortunate to have the health care coverage we have through Lori’s work. So yeah, I had a bit of fun, up until we crossed the border, at which point the two hours’ sleep of the previous night finally caught up with me.

It seems I wasn’t the only one…

When we arrived at the hospital in Udon Thani, Lori and Noe were efficiently ushered into the Emergency Room. It was Saturday evening and the ER in this city with a metro population of 450,000 was empty and silent.

They rolled Noe and Lori over to the triage section labeled “Pediatric Resuscitation” for the providers to utilize the child-size medical equipment. Still, Lori and I had an uneasy chuckle over that one.

After the staff took Noe’s vitals, We were shown our sumptuous digs in the ICU (Intensive Care Unit). There was a hospital bed, a couch, and sink. Okay, we’ll make it work, I thought. I started to unpack when one of the Thai nurses approached me and said, “Come. I show you where you stay.” Ah, so that’s how it works in Thailand. Hubby has his own room. I could get used to this.

I followed the Thai nurse in full “Madmen”-era nurse regalia (complete with mini-skirt) out of the ICU, down a ramp into an older building, and up to the seventh floor. The elevator opened and we stepped out into a dimly lit abandoned lobby of a disused hospital ward. It was apparent it had not been utilized for some time. The nurse led me down a dark hallway past a number of faux-wood grain doors from the 1970s or 80s to the last door on the left. “Your room here,” she said.

Granted, it was a very clean and serviceable space, aside from the 30-year-old decor and the fact that it was an old hospital room. Oh, if these walls could speak. Actually, I was quite happy they could not, or at least was hoping they wouldn’t after the lights go out.

“Would you like a key for your room?”

Hmm. An interesting question. Yes. Yes, I would.

A little off-put by the mild creepiness of being left alone in a decommissioned hospital room tucked away in an abandoned and decaying ward without mobile phone or internet access, I was somewhat comforted by the “Call for Help” button dangling above my bed. That is, until I returned to the lobby of the ward and spied the old call button unit sitting beneath an inch of dust with neither a power source nor a human attached to answer the call for help.

But hey, I’ve got a view…

After checking in with Lori and Noe down in the other building, the storm passed and I ventured out to forage for food.

On some level, I was expecting to step out into a bastion of Western fast-food restaurants given that we were now in wealthier, more industrialized, and more Western-leaning Thailand, but it was not to be. The general vicinity of the hospital on a Saturday evening offered very few dinner options. There was a Thai restaurant a block away, but I was silently hoping for something we couldn’t get in Vientiane.

So, I walked a few blocks past the Thai restaurant, then turned around and walked several blocks in the other direction on a storm-kissed jogging path along the banks of a picturesque urban lake. Fifty miles from Vientiane and a different world filled with garden-lined paths, traffic lines, decorative street lamps, and birdsong — it felt much more like the nicest parts of central Kampala or Durban than anywhere in Laos. Borders are a funny thing.

Ultimately, I ended up back at the Thai restaurant a block away from the hospital. Then, waited for 45 minutes for my food. One observation Lori and I have made in our few trips to Thailand is that Thai food seems to take far longer to prepare in Thailand than anywhere else we’ve been. At Thai eateries in Vientiane, it always seems to fly right out before the head has settled on our BeerLao.

Food in hand, I returned to Lori and Noe in the ICU. The little guy was justifiably out for the count, but doing much better overall. We’ll see what the night brings with Lori assigned to the child that gave us two hours of sleep the previous night, and me, assigned to my fatherly quarters, all alone in an isolated and abandoned old hospital ward.

Oh my goodness . . . THANK YOU for the spoiler! I’ve never read one of your posts faster. It had to happen, I suppose –the test of “what if”. It sounds like everybody passed that test! You know what to do, and so does everyone else, and you all made it through. I’m so, so, glad. I’m sorry for the sleepless nights and the stress (boy do I remember that!). Please keep us posted! Sending love and healing thoughts your way!